The agritech industry is editing plant genomes to feed a growing population, expand the produce aisle, and make tastier, more convenient food products.

Consider the groundcherry. Unlike its relative, the tomato, the groundcherry has never been fully domesticated. The plant’s sprawling growth and habit of dropping its small orange fruits on the ground before they’re ripe make it an awkward crop to cultivate, and its commercial presence is mostly limited to farmers’ markets.

But Joyce Van Eck of the Boyce Thompson Institute in Ithaca, New York, and Zach Lippman of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory are working to change that. Because they don’t have the option of domesticating the groundcherry over thousands of years of selective breeding, as agriculturists did with tomato plants, the researchers are using CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology to reproduce some of the tomato’s domestication-associated genetic changes. The pair recently used CRISPR to mutate the groundcherry equivalent of the tomato’s SELF-PRUNING gene, to try to rein in the groundcherry’s sprawling shoots (Nat Plants, 4:766–70, 2018). They’ve also edited a gene called CLAVATA, which controls fruit size, to generate larger groundcherries.

By making these and other modifications, the researchers aim to develop a groundcherry that can be mass-produced and sold as “the fifth berry crop,” Lippman says, alongside blueberries, raspberries, strawberries, and blackberries. (See “Zach Lippman Susses Out How Gene Regulation Affects Plant Phenotypes” here.) In doing so, Lippman and Van Eck, both of whom consult for the agritech company Inari Agriculture, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, join many other researchers and entrepreneurs hoping to use CRISPR-Cas9 to tinker with plant genomes in pursuit of goals such as expanding the diversity of produce in the supermarket and improving crop yield for a human population expected to reach 10 billion by 2050.

“You’ve got essentially arable land being taken out of production to build cities and towns,” says Oliver Peoples, CEO of agritech company Yield10 Bioscience, based in Woburn, Massachusetts. “At the same time you need to increase food production to feed the inhabitants of all those cities and towns. So clearly the only way that that works is that every acre of land has to become more productive.”

The potential of gene editing to address these problems has taken hold in the agricultural industry, with new companies hoping to capitalize on the technology sprouting up every year. “We can identify a handful [of companies] currently, but going forward that number will rise, perhaps even triple,” says Matt Crisp, CEO of Benson Hill Biosystems, an agritech company based in St. Louis, Missouri.

There have been a handful of regulatory successes, too. Since 2016, when a CRISPR-edited non-browning mushroom received the green light from the United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA-APHIS), the agency has also confirmed that CRISPR-edited corn, soybeans, tomatoes, pennycress, and camelina would be free from some of the red tape associated with other genetically modified organisms (GMOs)—though they may be subject to regulation by the Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency at a later date.

While none of these CRISPR-edited crops have yet made it to market, new plants are being edited all the time: last year alone, for instance, published research included efforts to tweak the genomes of carrot, cacao, and lettuce. “We regularly eat between 50 and 100 food products from 50 to 100 different crops,” says Haven Baker, cofounder and chief business officer of North Carolina-based agritech company Pairwise. Despite some concerns and uncertainty about the regulatory future of genome-edited food, “there’s CRISPR research going on in almost all of them.”

Engineering better plant products

Genetic improvement of crops has long been a goal for the agritech industry. But before CRISPR, most companies were limited to using transgenes—an approach that Tom Adams, cofounder and CEO of Pairwise, calls “a little bit of a blunt instrument.” Researchers couldn’t control where in the genome inserted transgenes landed, so they’d have to screen many plants until they found one in which the transgene had wound up in a good spot. While more-recent approaches, such as zinc finger nucleases and TALENS systems, have allowed researchers to edit specific genes, those techniques are expensive and still lack precision.

“Then CRISPR hit the scene, and it is fast and easy and inexpensive and gives great results,” says biotech expert and consultant Vonnie Estes, who worked for Monsanto in the ’90s and later for CRISPR-championing biotech Caribou Biosciences.

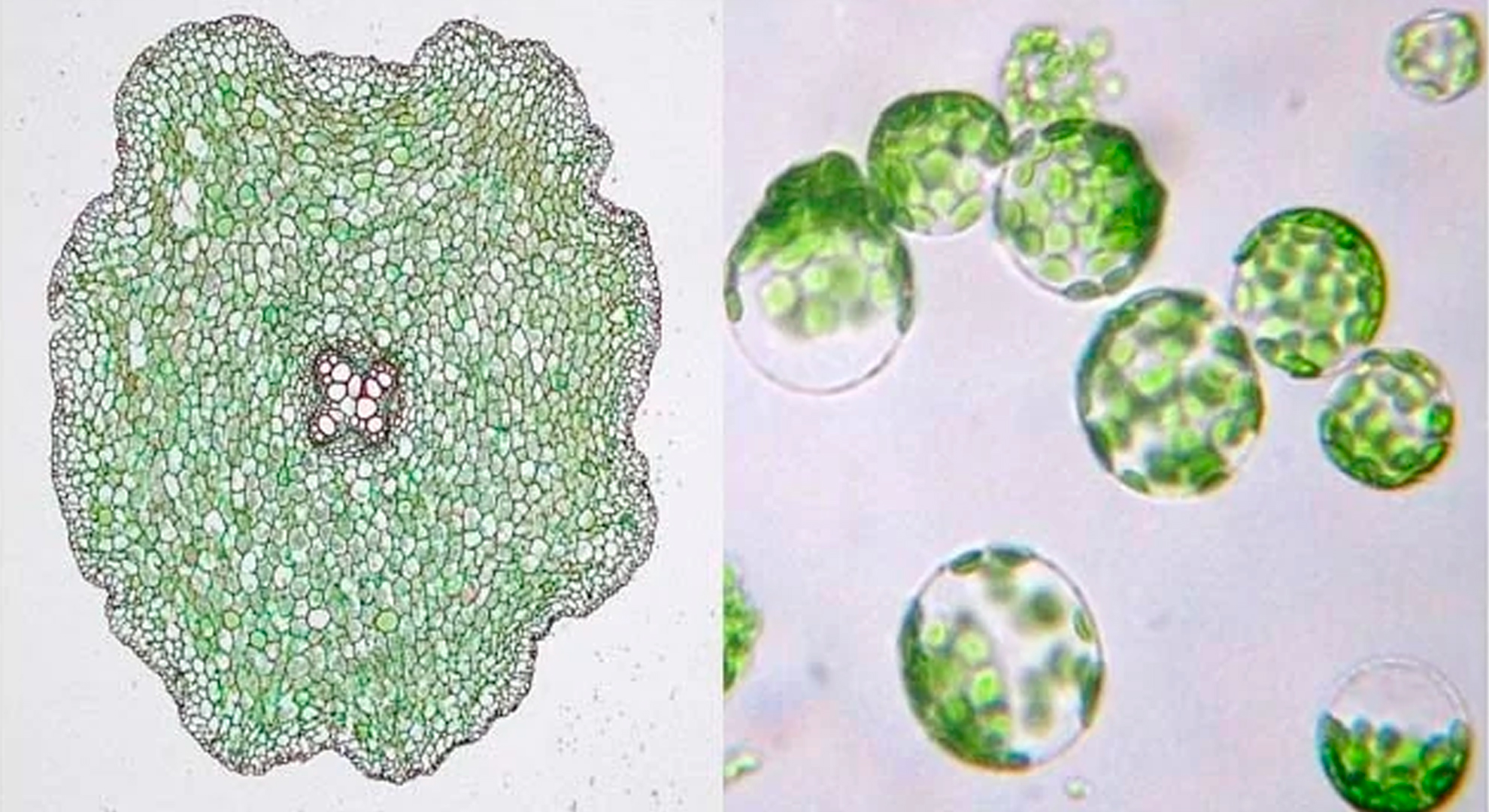

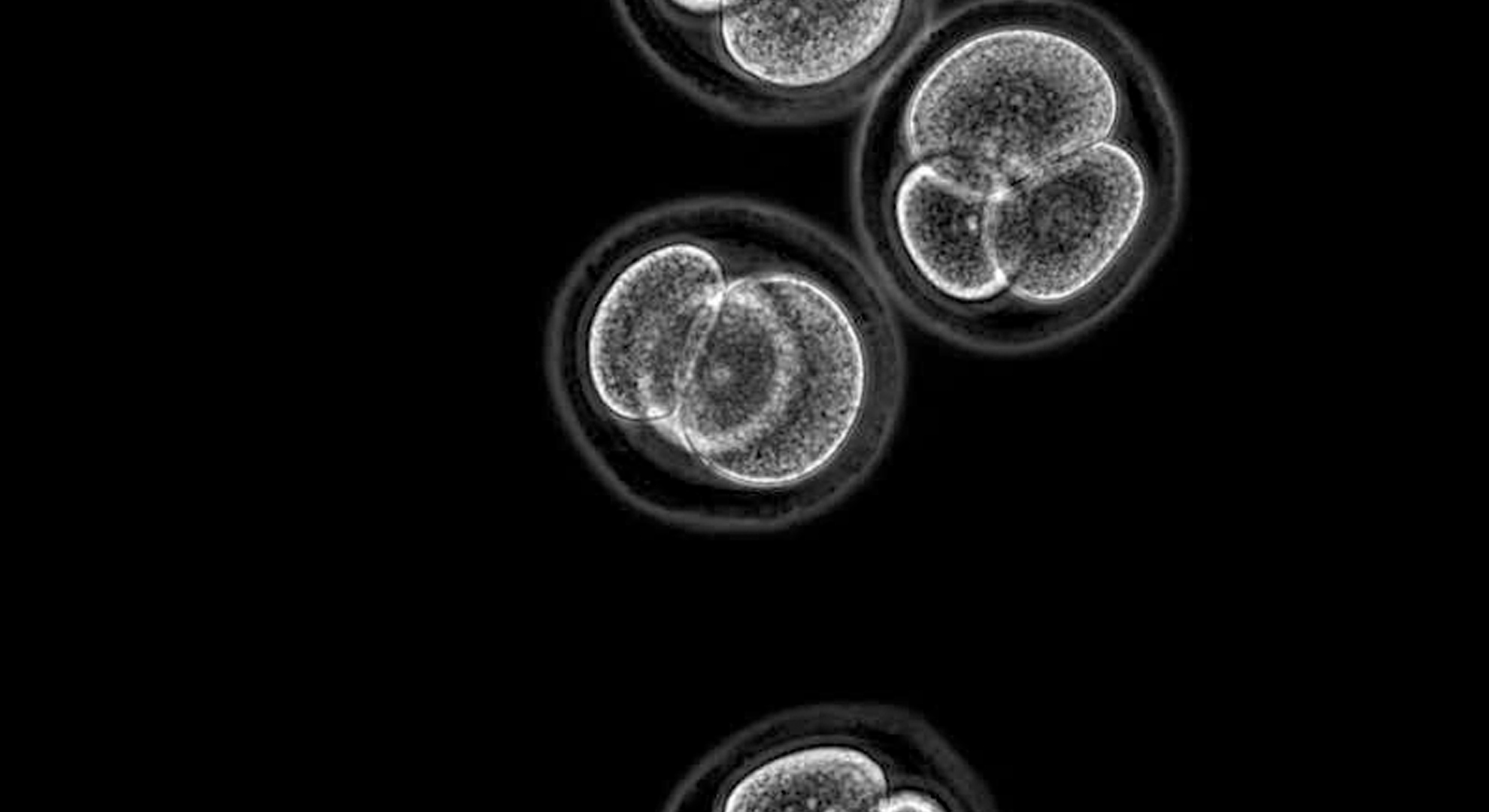

Researchers can use various techniques to insert CRISPR technology into plant cells: a gene gun to shoot the DNA or RNA in on tiny gold pellets, for example, or Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a crown gall bacterium and plant pest that inserts its DNA into plant genomes. A third approach is protoplast transformation, in which plant cells missing cell walls are transformed with CRISPR constructs. Transformed cells can then be cultured and eventually grown into plants.

Several companies are using these techniques to boost plant productivity. Yield10, for example, aims to improve the yields of crops such as canola and soybeans, and increase the oil content of these and other oilseeds. Company researchers are currently working to develop a variety of the yellow-flowered oilseed Camelina sativa, in which three genes, whose identities are proprietary, have been inactivated. Yield10 recently announced encouraging greenhouse results suggesting that these triple-edited camelina lines could increase the oil content of seeds, and plans to start field tests of the lines sometime this year.

The rules surrounding the regulation of CRISPR-edited crops are still in flux.

Pairwise, meanwhile, is focusing on making fruits and veggies more popular among consumers. The company, which started operating in 2018 and has so far attracted $25 million in investments, aims to shift people away from junk food by offering convenient produce. Just consider the success of easy-to-eat foods such as seedless watermelon, or baby-cut carrots (which are whittled down from normal carrots by machinery), suggests Adams. “When baby carrots got introduced, it basically doubled consumption of carrots and people were willing to pay for those carrots,” he says—“about five times as much as they pay for carrots that haven’t been made babies.” The company plans to use CRISPR-Cas9 and base-editing technology developed by Pairwise team member David Liu of Harvard University to make other fruits and vegetables easier to snack on. Pairwise won’t disclose information about specific products in development—but their first products should be on the market in four to five years, Adams says.

CRISPR could also be used to make tastier products, notes Benson’s Crisp. In traditional breeding, farmers tend to select plants with traits that benefit either the consumer or the farmer, he says. For example, some tomatoes can be shipped long distances, benefiting growers, but don’t taste very good, disappointing consumers. A goal for gene editing would be to engineer a tomato that has high yield, ships long distances, and tastes like it came from the garden, Crisp says.

One of the first CRISPR’d crops to hit the market might not be a food product at all, though food applications will likely follow. The crop is waxy corn, a variety edited to contain elevated levels of amylopectin and reduced levels of amylose via deletion of the gene Wx1. High-amylopectin cornstarch could improve freeze-thaw properties of frozen foods and make canned foods and dairy products creamier—though its first application, says a spokeswoman from Corteva Agriscience, the agricultural division of DowDuPont, will likely be as an adhesive to stick labels to bottles. Corteva expects that products containing the CRISPR’d starch, starting with adhesives, will be available within the next year or two.

To aid identification of genes underlying traits such as waxiness or sprawl, Benson, which has raised nearly $95 million from venture capitalists since 2012, has developed a software system called CROP-OS. The system has three main applications: Breed, to predict the outcomes of breeding different strains; Reveal, to find potential transgenes from other species; and Edit, to bring together information about different strains of crops, their genes, and their characteristics so that researchers can plan genome editing to suit their goals. Once collaborators have chosen the genes they want to edit, Benson either does the editing for them using Cas9 alternatives Cpf1 and Cms1, or, more often, ships them a CRISPR toolkit so they can do it themselves, Crisp says.

A selection of companies using gene-editing techniques for crop improvement

| Company |

Location |

Year Established |

Selected Tools/Services

|

Focus Crops |

| Benson Hill Biosystems |

St. Louis, MO |

2012 |

CROP-OS software; gene editing using CRISPR-Cpf1 and -Cms1 |

Row crops edited for higher yield, stress resistance, and herbicide tolerance |

| Corteva (agricultural division of DowDuPont) |

Wilmington, DE |

2018 |

CRISPR-Cas9 |

Waxy corn modified for altered starch composition |

| Pairwise |

Durham, NC |

2018 |

CRISPR-Cas9 with base editing |

Row crops such as corn and soybeans with increased productivity, disease resistance; more-convenient fruits and vegetables |

| Syngenta |

Basel, Switzerland |

2000 |

CRISPR-Cas9 |

Corn, soy, wheat, tomato, sunflower, modified to increase yield |

| Tropic Biosciences |

Norwich, UK |

2016 |

CRISPR and other techniques |

Disease-resistant bananas, decaffeinated coffee |

| Yield10 Bioscience |

Woburn, MA |

2015 |

CRISPR-Cas9 |

Camelina engineered for higher oil content |

Regulating CRISPR-edited crops

As industry researchers explore the opportunities to genetically improve consumer crops, they’re keeping a close eye on the regulatory landscape that governs their ultimate success, says Estes. The biotech industry is “at a kind of a weird point right now,” she notes. “There’s so much work that’s being done in universities. . . . But as far as getting it into commercial companies and having them bring it to market, everyone’s sitting on the fence a little bit and a little nervous.”

That’s because the rules surrounding the commercialization of gene-edited crops are themselves in flux, as regulators struggle to keep up with rapid technological developments. Older, transgenic approaches involving the introduction of foreign DNA are tightly regulated in the US and Europe, leading to considerable costs for companies trying to market transgenic products. “Regulations around approval for the use of a plant species that’s been genetically engineered can take up to a decade or more and cost up to $130 million per genetic change,” says Peoples. So it’s only something companies can do if they have a lot of money to invest—and they’ll only do it for a crop that’s going to make a lot of money, such as corn or soybeans.

Products generated by gene-editing techniques such as CRISPR have historically not been subject to the same rules, meaning that a larger number of smaller companies can afford to get into the sector. Genome editing has “really democratized this sort of innovation in the agricultural space in enabling smaller companies like Yield10 and others to begin to really make an impact using new approaches that perhaps the ag majors hadn’t tried in the past,” Peoples says.

However, the days when gene-edited crops circumvent regulation may be drawing to a close. Last July, the European Court of Justice ruled that, going forward, gene-edited crops would be subject to the same stringent regulations in Europe as transgenic plants—a ruling that surprised many researchers and went against the counsel of the court’s own advisor on the subject. The court based its decision on the fact that gene-edited plants, like other GMOs, change organisms’ genetic material in ways that do not occur in nature.

Crisp says that he and other researchers in agritech were sorely disappointed by the ruling, and there are now moves to try to change course. The European Commission’s chief scientific advisors issued a statement highlighting the impossibility of determining whether a mutation occurred through gene editing or through natural mutation and suggested it would be better to focus on the safety of the product, rather than on the process by which it was created. (See “Opinion: GE Crops Are Seen Through a Warped Lens” here.)

Regulation has so far taken a different path in the US. In 2016, lawmakers passed the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Law, which required manufacturers to label products containing “bioengineered” food—defined as food “(A) that contains genetic material that has been modified through in vitro recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) techniques; and (B) for which the modification could not otherwise be obtained through conventional breeding or found in nature.”

Jennifer Kuzma, codirector of the Genetic Engineering and Society (GES) Center at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, tells The Scientist that part (B) of this definition was probably added “in order to exclude gene-edited plants” from the labeling requirement, and thus reduce regulatory red tape for these products. Similarly, a draft ruling issued last May about how the requirement would be implemented omitted mentions of “editing” or “CRISPR,” and the final ruling, issued in December, does not explicitly state that gene-edited foods will be subject to the disclosure requirements.

In another regulatory win for producers of CRISPR-edited crops, last March, the US Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue announced that the USDA would not regulate crops that “could otherwise have been developed through traditional breeding techniques as long as they are not plant pests or developed using plant pests,” again clearing the way for plants created through genome editing. (Even methods that rely on A. tumefaciens can skirt the pest clause by ensuring that no bacterial sequences remain in the genome of the final product.)

Of course, not everyone in the US believes that less regulation is better. As Kuzma writes in a recent review article, most consumers want the government to ensure the safety of genetically modified crops, and 60 percent of biotech experts she surveyed support some kind of pre-market oversight. Kuzma, who says she is neither for nor against the development of gene-edited crops, notes that some regulation, as well as clear labeling of gene-edited foods, is necessary to avoid a repeat of the consumer backlash against GMOs, and that these measures are in the long-term interests not just of consumers but also of agritech companies.

Estes believes consumer backlash will be less of an issue once appealing CRISPR’d crops, such as the groundcherry, start to hit shelves. “Some segments of people aren’t going to care as much about how it was done,” she says, “as long as they get this amazing thing they get to eat.”

Ashley P. Taylor is a freelance writer and science journalist in Brooklyn, New York.